About

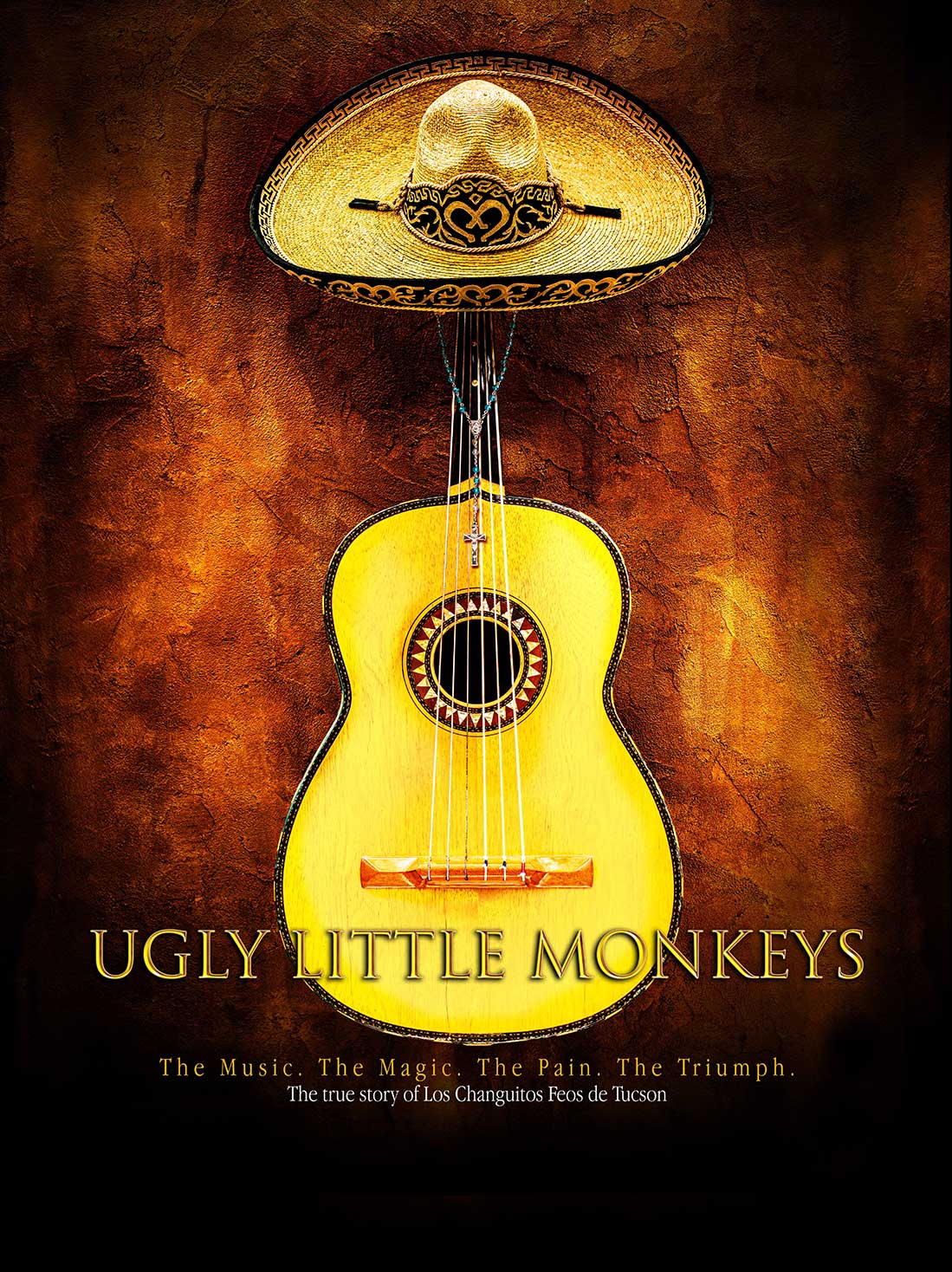

The Film

It was 1964. Assimilation was rampant in Mexican/American homes. Your parents named you Roberto but everyone knew you as Bobby. Speaking Spanish in the school system drew severe corporal punishment. Your parents and grandparents were prideful of their Mexican heritage but, because of the prejudice they experienced at the hands of bigots and racists the language and customs of that heritage was not passed on to their children.

As a kid you were swept up in the, “British Invasion” The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Herman’s Hermits. On television your grandmother watched Mexican soap operas and you snickered and ridiculed her to your friends because she kept you from watching “Leave It To Beaver, The Andy Griffith Show and Bonanza.”

Bars and Mexican/American social gatherings were the sites Mariachi music was relegated to. In the movie industry the art form was used as an object of ridicule played by drunken, slovenly stereotypical characters. Even though it was portrayed in that fashion, the familiarity of it invoked a sense of concealed pride in the older generations of Mexican/American homes. When heard at social events the moment the Mariachi launched into the first notes, it would give the listeners chills and make the hair on their arms stand up. The dichotomy of those sentiments would permeate a young Mexican/American’s existence. One of those sentiments had to dominate and it was the former that prevailed. Parents encouraged assimilation and caused Mexican/American youth to strive to become the, “All American Boy.”

The predominant faith within the Mexican/American community in Tucson, Arizona was and has been Catholicism. Not exclusive to that community the practice of it in the nineteen-sixties was a faith practiced by many racial groups. Mexican/American young men were raised in it and attended Catholic schools and many became altar boys as a result. Because the faith was inclusive the practice of it was not something Mexican/American youth were ridiculed for. There was a familiarity with it and Mexican/American parents were devoted to it.

Into this zeitgeist came an Irish/American priest. Hailing from Schenectady, New York Father Charles H Rourke was an accomplished jazz pianist that had shared the stage with Sarah Vaughn, Duke Ellington and was said to be friends with Peter Nero. He had served in the U.S. Navy and studied Pre-Med at Union College of New York. He was young, handsome and eloquent and his homilies were said to be awe-inspiring. His charm was intoxicating and he was welcomed into Mexican/American homes with a status reserved only for those deserving the highest reverence.

When he displayed his musical qualities in schools the Mexican/American youth were immediately drawn to him because he played a form and style that they had been encouraged to admire. He had a passion for assisting in the positive development of at-risk youth hosting a radio program dedicated to youth awareness. When he was introduced to Mariachi music he fell in love with it and hit on the idea of using the form to recruit young men and begin a youth Mariachi.